Sarah Miller Author Essay

Let me tell you a secret: the research is the best part. I’m supposed to say that it’s the writing, but it’s not. Writing is work. It’s necessary work if I want to share the stories that enthrall me, but it’s hard work. Research, though? That is a playground.

The most fascinating thing, the thing that nothing but research reveals, is how stories evolve. Even nonfiction, which is built of facts, is affected by our perceptions. As the years and decades pass, the way we look at people and events undergoes drastic transformations, even when the facts remain the same.

For instance, Lizzie Borden is perceived today as an axe-wielding psychopath, even though the facts inform us that she was a Sunday school teacher who was acquitted of the murder of her father and stepmother.

Or consider the Ontario government’s move to take custody of Yvonne, Annette, Cécile, Émilie, and Marie Dionne—the first surviving quintuplets in history—and raise them as wards of the crown. In 1934, that decision looked like a heroic act of protection for five premature babies, but eighty years later, it reeks of exploitation.

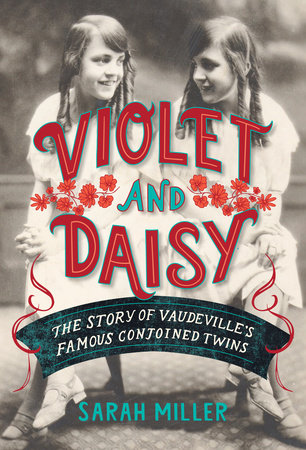

And then there’s Violet and Daisy Hilton. These conjoined twin sisters were abandoned by their mother and abused and exploited by their guardians from the time they were three weeks old, and no one at that time batted an eye. At least, I was pretty sure that’s what happened. Turns out, Violet and Daisy had a habit of stretching the truth for the sake of publicity almost as often as they themselves had been lied to as children.

How do you suss out the truth in cases like this? Dig. And keep digging until you hit facts that won’t yield. Then dig a little more, just to be sure.

My career began with historical fiction and might have continued exclusively in that direction if I hadn’t started reading about the Borden axe murders. Once I delved deep enough to discover how drastically the Lizzie Borden of pop culture differs from the verifiable facts about her, the challenge of uncovering the real Lizzie instantly had much more appeal than (re)creating an imaginary one. So I read the Borden murder trial transcript. All of it. As well as the witness statements, inquest testimony, and preliminary hearing transcript—2,578 pages in all. That was not 100 percent fun, but it’s how I learned that if you go back to the bedrock facts and begin creeping steadily forward—chronologically, if possible—you start to catch glimpses of how people’s memories metamorphose, even when they’ve sworn to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

Next came the Dionne Quintuplets and four trips to North Bay, Ontario, with a stop at the Archives of Ontario in Toronto. Imagine reading the handwritten diaries of the first nurse who attended those five identical babies. Imagine slipping on white cotton gloves and opening folder after folder of original photographs of Yvonne, Annette, Cécile, Émilie, and Marie Dionne—1,400 images in all. At the Callander Bay Heritage Museum, I got to sit at a table covered with boxes and sift through snapshots, blueprints, and scrapbooks stuffed with newspaper clippings. Every box was a surprise—I swear to you, it felt just like Christmas. The sisters’ baby clothes were hanging on the walls, and the basket they were placed in the night they were born was in a glass case. No less dazzling, and even more valuable to me, were long-neglected newspaper and magazine interviews with the Dionne sisters and their parents and siblings, which enabled me to let their voices be heard for the first time since the 1930s.

These trips aren’t just about learning what can’t be learned elsewhere. They’re also about feeling what can’t be felt elsewhere. It’s one thing to read about how five fragile preemies were whisked out of their family’s farmhouse and into a custom-made hospital across the road. It’s another to stand outside of the barbed-wire fence that surrounds the remains of the hospital and think about what that fence meant to not only the five children locked inside, but the rest of their family, who were locked out.

Pondering the evidence in the Borden case for a year, wondering how all those tiny pieces fit together, is not the same as standing in Fall River’s Oak Grove Cemetery before four headstones marked Andrew, Abby, Lizbeth, and Emma (Lizzie’s sister). It’s only in the cemetery that you fully realize that the Borden murders are much more than a puzzle—they were crimes that brought about the destruction of an entire family.

I don’t always get to go in search of one-of-a-kind artifacts and experiences, though. There’s a lot of sitting in one spot, turning virtual pages until, if I’m lucky and tenacious enough, I uncover something vital that nobody’s looked at in decades. In the National Library of Australia’s digital collection, for example, I stumbled across a 1915 newspaper article protesting Violet and Daisy Hilton’s treatment at the hands of their guardians that made me stop and blink in disbelief, because somebody did care. Somebody saw them not as freaks, but as eight-year-old girls. In its own way, that was as affecting as standing in front of the barbed-wire fence in Ontario.

Then, to sit down in front of a blank page and condense all of that information and all of those experiences into a couple hundred pages—that’s when the real work begins.