Kathleen Glasgow Author Essay

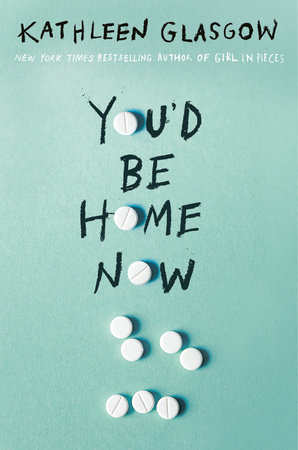

I’m no stranger to difficult things. I’ve written young adult novels about self-harm and depression (Girl in Pieces) and grief (How to Make Friends with the Dark). Bits of these books are drawn from my own life experiences; I give my characters some of my feelings, but their stories belong to them. I write for teens because when I was a young adult, struggling with mental health issues, reading novels with characters who were depressed or addicted or hurting made me feel less lonely. Books can show you how not alone you really are. They can be a safe haven in a world whose language and rules often seem beyond your grasp.

My new novel, You’d Be Home Now, is loosely inspired by Thornton Wilder’s classic play Our Town, long one of my favorite plays. One line in particular has stayed with me over the years. Emily Webb implores her mother, “Oh, Mama, look at me one minute as though you really saw me.” Isn’t that what teens want from the adults in their life? To be seen as they are, not as they are supposed to be. Adolescence is messy and complicated and quite often painful, with tinges of joy in between. I feel like we forget that when we become adults and parents and caregivers.

There was a lot to consider when reimagining Wilder’s play, which is set in the small town of Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire. What would Grover’s Corners look like today? Who would a reimagined Emily Webb be? And what to do with the character of the Stage Manager, who speaks directly to the audience and seems to know everything about everything, including the futures of the characters?

Step one: The Stage Manager becomes a teen Instagram poet named Mis_Educated whose posts reveal the town of Mill Haven’s secrets and in whose comment section teens feel safe talking about the way they really feel about life and all its complications.

Step two: I feel certain that if Wilder wrote this play today, Grover’s Corners would be reeling from the opioid crisis. After all, Wilder didn’t shy away from discussing suicide and alcoholism in Our Town. He was no stranger to difficult things, either.

Step three: Emily becomes Emory Ward, facing the fallout from her brother Joey’s drug addiction and the connected death of a classmate.

Emmy is drowning under the weight of taking care of Joey after his return from rehab. She’s always been “the good one” in her family. Joey has always been “the bad one.” Those roles are destroying them. I’ll bet you know an Emmy: always taking care of everyone and putting their own emotional needs on the back burner. Maybe you were an Emmy in your family. Or maybe you were a Joey: always the disappointment, dragging down the family and sucking all the energy from the room. Maybe there’s a Joey in your family.

I’ve been Emmy and I’ve been Joey. They’re both sinking under the weight of adult expectations. No one really sees them for who they are. Emmy is expected to caretake Joey’s sobriety and get good grades. Joey returns home to a doorless room and an endless list of rules. If he can’t abide, he’ll have to leave the house. It’s an unmanageable situation for them both.

It was important for me to write about Emmy’s love for Joey as well as her frustration and guilt over his situation. I’ve been in recovery for years and I still vividly remember people begging me, “Why can’t you just stop already?” In writing Joey, I wanted readers to understand that it isn’t that simple. I wanted them to understand where’s he’s coming from, what he feels, why he does what he does and why he can’t stop. (Spoiler alert: shaming people does not eliminate addiction.)

Addiction directly affects the mental health of everyone in its orbit. Family member, friend, teacher, community. It is not a faceless disease, and yet we often treat it as such. “They did it to themselves.” “They could get better if they wanted to, but they don’t.” “Not my problem.”

But just like in Mill Haven (the reimagined Grover’s Corners), it is our problem. Those aren’t ghosts under Frost Bridge in You’d Be Home Now. They’re people, struggling to be seen and to survive. Addiction is a public health crisis. It’s in your house, your neighborhood, your community, your schools. And the collateral damage is kids like Emmy, whose mental health is fraying under the strain of trying to keep everything “normal.” There is no normal. There is only survival, and hoping the next day is better than this one. As Emmy notes in her school essay at the end of You’d Be Home Now, “Sometimes your life falls to ash and you sift through, waiting for the pain to pass, looking for the remnants in the debris, something to save, when really all you need is right there, inside you . . . love remains.”

I wrote You’d Be Home Now for the Emmys and the Joeys, kids faltering under the weight of so many heavy things. Because life is messy and complicated and painful, and books should show that. Like Emmy says, “We could all probably be a little more benevolent in life. We all live here, after all. We all share the same mighty good company of the stars at night, and everyone deserves kindness, and survival.”