Let’s Talk About It

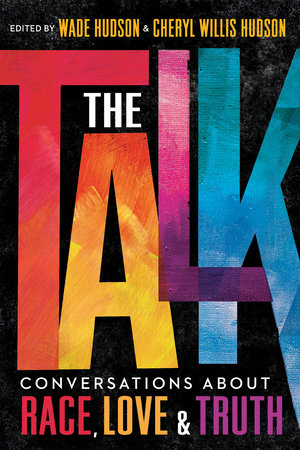

Cheryl and Wade Hudson, editors of The Talk: Conversations about Race, Love & Truth, share why we need to have "the talk".

Talking about race, sex, social injustice, or other difficult subjects has always been uncomfortable. Many parents and teachers wonder whether they are equipped to engage children in these difficult conversations, particularly when they are struggling to determine how they themselves feel about the subject. Desiring to protect their children from the perceived fallout, some choose to not have “the talk” at all.

It is not so easy to shelter young people, however. Children are impacted by events, incidents, and attitudes just as adults are. They get their information from friends, from television, and from social media. This information often comes without perspective or context. That’s why having “the talk” is so important.

As parents, we recognized that early on. We knew we had to help prepare our two children as best we could, as written in the introduction to The Talk: Conversations About Race, Love & Truth, with “the tools to make their way as safely as possible in a society that is too often hostile to them simply because they are African American. Especially as sometimes that hostility leads to the loss of Black life.” It is a responsibility that most African Americans assume determinedly. Our parents certainly did. For us, there wasn’t just one talk but many talks.

We conceived of The Talk in 2018, while we were preparing for the launch of our first anthology with Crown Books, We Rise, We Resist, We Raise Our Voices. That book was a conversation with young people during the challenging, contentious, and frightening period that followed the 2016 election. In it, creators used words and images to encourage, comfort, and reassure, and to let young people know we love them, all of them. To remind them that we have faced difficult periods before, and we would get through this one. We Rise made it obvious how important these conversations are, and also accentuated that conversations need to involve all of us if we are to become the beloved community that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. talked and wrote about. The Talk seemed like a natural follow-up.

How then, do we begin to approach having these important and crucial conversations—whether at home, on the job, or in classrooms?

We suggest beginning from exactly where you are. As educators, librarians, or parents, acknowledge your discomfort. We urge you to look at this anthology as a resource filled with a variety of perspectives that are available as starting points to begin important conversations. The talks within this collection are multicultural and intersectional in nature, and can be used in a variety of ways. There are so many opportunities to employ critical thinking when experiencing these pieces and during the conversations that are sure to follow.

The language of our national discourse is constantly changing. What do our children know about systemic racism? Injustice? Fairness? Equality? White privilege? Diversity and inclusion? While they might not have the jargon readily at hand to express their observations and experiences, those situations and feelings do exist. Millions of people around the world were moved in profound ways by the brutal murder of George Floyd as well as other killings of unarmed African Americans. So were children. The response has inspired all kinds of people to open themselves up to learn more about social injustice, racism, and white privilege. In so many ways, The Talk is timely and appropriate.

This anthology shows that important conversations about who we are and what we believe about ourselves and others are not limited to Black families but involve a multitude of cultures within the fabric of America. Contributors to The Talk use authentic stories about their personal experiences to provide windows and mirrors for readers.

- Social studies teachers may use Traci Sorell’s and MaryBeth Timothy’s story “The Way of the Anigiduwagi” to discuss how sovereignty and Indigenous culture are affirmed in spite of default “Indian” stereotypes.

- Language arts teachers may use “Tough Tuesday” by Nikki Grimes and Erin K. Robinson or Meg Medina’s and Rudy Gutierrez’s “Hablar” to explore how words can be used in both harmful and healing ways.

- Media specialists may point to Valerie Wilson Wesley’s and Don Tate’s “Never Be Afraid to Soar” or Duncan Tonatiuh’s “Why Are There Racist People?” as sliding glass doors to begin historical research.

- An untitled essay by Daniel Nayeri may be used as a creative writing prompt to illustrate how silence or a refusal to talk may impact how a person is judged within various cultures.

- Essays such as Christopher Myers’s “Mazes” and Grace Lin’s “Not a China Doll” provide analyses of Greek and Asian mythologies by retelling the stories and reinterpreting them in a contemporary American vernacular.

- Whether talking about friendship (“F.R.I.E.N.D.S.” by Torrey Maldonado and Natacha Bustos), being stopped by the police (“Ten” by Tracey Baptiste and April Harrison), economic disparity (“The Bike” by Wade Hudson and E. B. Lewis), physical appearance (“Remember This” by Renée Watson and Shadra Strickland, “I’m a Dancer” by Sharon Dennis Wyeth and Raul Colón, and “My Olmec” by Selina Alko), confronting outright racist stereotypes (“Handle Your Business” by Derrick Barnes and Gordon C. James), examining White privilege (“Our Inheritance” by Adam Gidwitz and Peter H. Reynolds), or navigating religious intolerance (“The Road Ahead” by Minh Lê and Cozbi A. Cabrera), The Talk offers a broad range of conversations about race, love, and truth. Dive in and don’t be afraid to explore even further.

The time is now. SO LET’S TALK!