Victoria Lee Author Post

When I was in high school, I ate all my lunches in the library. Most of my friends weren’t on the same lunch schedule as I was, plus my creative writing independent study was the period right after lunch, so it kind of made sense—I could go in early, eat there, and read. Then, when the bell rang, I’d be ideally situated to start working on my book. I got to know the librarians, a couple named Mr. and Mrs. Larson, pretty well during that time; they’d frequently bring in secret doughnuts that were only meant to be shared with those of us who basically lived in the library, who came to school early so we could browse the stacks, who checked out so many books every week that the Larsons had to raise the weekly limit just for us.

I was also struggling with depression.

And maybe that had more to do with my library lunches than I could admit.

Felicity, the main character in A Lesson in Vengeance, also struggles with depression. I can see reflections of my younger self in her: the way she self-isolates, how she constructs these narratives for her own life, ones she thinks are maybe more palatable than the truth. She, like myself, loses herself in literature, in other worlds that aren’t her own, where she doesn’t have to exist in the space of her own body and life.

Sometimes I wonder how much of that the Larsons recognized in me. I missed several weeks of school at various points when I was hospitalized for suicide attempts. I wonder if they knew why I was gone. Either way, they were a touchstone for me throughout high school. By the end, I had started calling them my parents, because in a lot of ways it felt like they were—always ready with good advice or a warm embrace or even just a fresh Krispy Kreme.

They’re the kind of people I think Felicity needed, too. Maybe if she’d had her own Larsons, she would have known on some level that people existed—particularly adults—who were there for her, who cared enough to still be there when she rose out of the mire of another episode.

When I graduated high school, though, I had to finally bring back all the library books I’d been sneaking out of the media center for the past four years. (Even the Larsons’ inflated check-out limit was not enough for me.) I left them in several huge black trash bags just inside and crept off, humiliated. I didn’t leave a note. I figured they had no way of knowing it was me; those books could have been left there by anyone. But then the phone rang a week later and my mother—my biological mother, not my library mother—picked up. It was Mrs. Larson.

She wanted to thank me for returning all those books.

Meet Savanna Ganucheau!

Meet Savanna Ganucheau! Savanna is the artist behind the new graphic novel adaptation of Jennifer L. Holm’s Newbery Honor–winning Turtle in Paradise.

Savanna got her start in comics by self-publishing and selling her work in small comic book shops around New Orleans. Savanna’s artwork has appeared in notable publications, including Jem and the Holograms, Adventure Time, and Lumberjanes. Her first graphic novel, Bloom, is published by First Second. Here, Savanna shares her process for bringing Turtle in Paradise to life.

What went into presenting an accurate depiction of 1930s Key West?

GANUCHEAU: I did a lot of research, but Jenni was also able to help me a lot. She had done tons of research for the novel, and I was able to take advantage of that. I had a great time researching clothing. I stayed away from catalogs of the time and focused more on photos from the 1930s of children in rural areas.

Did any of the characters, creatures, or locations present a particular challenge for you?

GANUCHEAU: Definitely the docks. Boats were another thing that was particularly challenging for me. The sponging boats used in 1930s Key West were rarely photographed, so it was difficult for me to find a comprehensive reference that wasn’t a vague side view. And in the 1940s, Key West saw a huge boom in the shrimping industry, which took over most of the sponging industry, so I couldn’t even use photos taken at a later time. Basically, if I saw shrimping boats in a picture, I knew it was from the 1940s and didn’t use it.

Why are comics such a good medium for historical fiction?

GANUCHEAU: Showing our past through images and stories (real or fictional) is a wonderful opportunity for people to relate to historical events in a very human way. I think people have trouble being invested in certain eras of time. Showing the day-to-day life and interactions between characters can help people feel involved in that history and be willing to learn more about it.

In this new adaptation, the color palette and shapes of panels change when looking at the past. How did you and colorist Lark Pien choose how to differentiate the timelines?

GANUCHEAU: We talked about a lot of options when it came to differentiating the flashbacks from the present. In addition to changing up the panel borders, I told Lark I wanted to evoke a sepia-tone feel, and we agreed that we wanted it to feel more creative. Lark did amazing work making the colors memorable. I think what she did with the pink color hold on the balloons is unique and makes the flashback pages stand out.

On page 43, we see Key West as the kids explore the docks. How much of this was drawn from reference materials, and how much was imagination? Telling a story set in a real place, did you feel pressure to stay accurate to the historical setting?

GANUCHEAU: Pressure from myself, for sure. Haha. I absolutely wanted it to be accurate. I’m a huge fan of historical fiction, and while there are a few anachronisms in the book (clothing, mostly), I tried to make it as accurate as I could. The docks were particularly hard because they simply do not exist in the same capacity as they did in the 1930s. And there’s really only a small trace of their layout in the documents I found. (I found some Sanborn Maps that gave me a vague idea.) For this scene, I used a lot of souvenir cards from the 1930s to get a sense of how the turtle kraals looked. In fact, panel one is heavily inspired by one of those cards.

Q&A with Unbound Creators

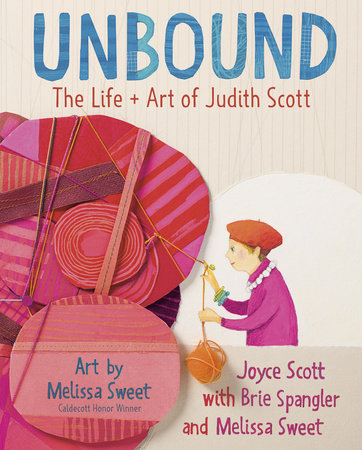

Unbound: The Life and Art of Judith Scott By Joyce Scott with Brie Spangler and Melissa Sweet; illustrated by Melissa Sweet

A moving and powerful introduction to the life and art of renowned artist, Judith Scott, as told by her twin sister, Joyce Scott and illustrated by Caldecott Honor artist, Melissa Sweet.

Judith Scott was born with Down syndrome. She was deaf, and never learned to speak. She was also a talented artist. Judith was institutionalized until her sister Joyce reunited with her and enrolled her in an art class. Judith went on to become an artist of renown with her work displayed in museums and galleries around the world.

Poignantly told by Joyce Scott in collaboration with Brie Spangler and Melissa Sweet and beautifully illustrated by Caldecott Honor artist, Melissa Sweet, Unbound is inspiring and warm, showing us that we can soar beyond our perceived limitations and accomplish something extraordinary.

This book is such a work of art and of love. The care and collaboration really come through! Can you talk about the process of working together to create Unbound?

JOYCE: All of us were aware that this book was something larger than the story itself, that the story of Judith’s art and life had the ability to change perceptions of disability and Down syndrome for both children and their parents who read with them. Each of us in our own way was dedicated to having the book be the best it could be and to having Judy’s story reflect the truth that there are gifts that lie within everyone.

BRIE: I really have to give true credit to both Joyce and Melissa for the beauty of this story and must give our editor, Erin, a standing ovation for shepherding this story of true sisterly love into the book it is today.

MELISSA: In crafting any biography, it’s the research that gives clues to the words and images. I read everything I could get my hands on about Judith, including Joyce Scott’s biography Entwined, books and essays, and reviews of Judith’s gallery shows. Early on in the process I went to California to research the Creative Growth Art Center and to talk with the teacher who was the catalyst for Judith creating her sculptures. When I walked into the center for the first time, I saw artwork on the walls and tables, spilling onto shelves. There was so much freedom and heart in every piece; it made me want to pull up a chair and make something for the pure joy of it. Once the manuscript was edited, I talked with Joyce about growing up with Judith, and she offered great photos for reference to use in the book. It was an honor to get to know Joyce and to hear the details of their childhood.

A spread from the dummy for UNBOUND

Joyce, can you share about some of your favorite memories of Judith, as well as some of your favorite pieces of her art?

A favorite memory of Judy and of our life together happened almost every evening. Her board and care home was only a block away, and I would show up just after dinner. She and I would cuddle together in her little bed where we would look at magazines and kiss the photos of handsome guys, play cards with our own very silly rules, use sign language only she and I knew, and be completely at home and at peace with each other. Never have I felt so at home and so loved. These were the happiest times of my life.

Two favorite memories involve Creative Growth, where Judy spent her days weaving and wrapping, creating extraordinary fiber sculptures. When I attended a preview of her very first show, I was moved to tears when I saw that she had made a piece which showed two figures who were obviously twins. I knew without a doubt that she knew who we were to each other. The second was when I showed her a photograph of the two of us as babies, not anything she’d ever seen before. She looked carefully and then pointed to the baby who was me and touched my face, then she touched the baby who was Judy and patted herself on the chest. She knew! How did she know? We had never looked at pictures together. How did she know?

Some favorite sculptures:

- A later set of twins with their arms entwined

- A very large piece that looks like a butterfly. I see it as a symbol of her flying free.

- A mysterious and powerful white mound that she made from taking all the paper towels from the bathrooms and wetting and wrapping them into this form. (The studio was closed, but Judy refused to leave and, without materials, found her own.)

- Her many pieces that look like cocoons or Egyptian mummies.

To learn more about Judith’s art and see examples, visit https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/judith_scott/ and https://creativegrowth.org/judith-scott.

Inside Creative Growth

Brie, how did you learn about Judith’s story and come to work on this project?

I knew of Judith’s works from the internet. I’d seen pieces of hers included in online retrospectives of outsider art. There’s a Twitter account that specializes in featuring women’s art and, one day, they highlighted Judith. I retweeted it. Erin saw my retweet, and that’s how the ball started rolling on my involvement in this picture book.

Melissa’s studio with the book underway

Melissa, we love hearing about the process of picture book illustration! Can you share more about this, especially the materials you used to bring Judith’s art to life?

One of the most rewarding things about working on a book about an artist (or anyone!) is to learn not just about their process, but finding the moment when they began to create, or invent, or have an “aha” moment. Re-creating those key moments is what makes a picture book biography accessible and allows readers to better understand that person, to find empathy and inspiration. It’s the essence of a story to my mind.

In this story, my quest was to illustrate the very moment when Judith began wrapping her first sculpture, which became my favorite piece in the book. I set up the materials Judith used and began making my own wrapped sculpture to use in the art. It was exciting to put myself in Judith’s shoes, not knowing how this piece would turn out.

Melissa beginning to play with an idea for the title page, introducing materials akin to what Judith might’ve used

Joyce, you learned so much about Judith and Down syndrome throughout her life. What is something you would tell others who are learning, and what is a hope you have for this book and its message?

I would hope that people reading the book will realize that, like Judy, people with Down syndrome or other disabilities have hidden talents and creative potential, that everyone has gifts to share. I hope they might realize that different does not mean less than. I would love for parents to become interested in places like Creative Growth and want to visit and perhaps support these art centers.

Fabulous clothing designed for the Creative Growth Fashion Show

Is there anything you had to leave out of the book? What was a major challenge to writing Judith’s story, Brie?

There was a lot of pain in Joyce’s memoir. Aching sadness. It was hard to translate the agony of having your twin sister stripped away from you at such a young age into words that retained the feelings but made the story approachable to the heads and hearts of children.

Detail of Judith first sculpture

Melissa, do you have a favorite spread in this book that you can share more about? What spread was the most challenging?

When it came time create the collages showing the students and teachers at Creative Growth and their art, I had the idea to use actual pieces of art from the students that have been printed in various publications. I am very grateful we had permission to use this art. It was the best way to make my art show what it feels like to be inside Creative Growth.

Melissa’s favorite spread showing Judith creating her first sculpture

Can you share more about how art has touched your life and why it is essential? What does Judith’s life and art mean to each of you?

JOYCE: Through Judy and Creative Growth, I have come to understand that art can provide a voice for the voiceless, and that creativity dwells in every human being. It only needs support and an opportunity for expression. At Creative Growth, surrounded by the creative energy and joy of the artists, I have come to believe that the most creative people may be those who have limitations in other areas and can create without the worries of paying the rent and putting food on the table, can create without wrapping every experience in words.

Through Judy’s art I have learned that art is its own language, perhaps far deeper than words, possessing shape and form, color and shadows, often born of our deepest joys and sorrows, expressing the inexpressible.

Being Judy’s twin, sharing our childhood and then her final twenty years of creative exuberance, has impacted my life in every way, perhaps more than anyone. Through her I knew love without judgment, and when with her, I too lived and loved in the moment. What a blessed person I am. I’ve often thought of her as our very own Buddha. It was her nature to live in the moment, to love with joy and abandon. She had no need for meditation or yoga. She was already there.

After being confined to an institution for thirty-five years, when finally given an opportunity, she seized the moment and created sculptures which have astonished the world. I feel so honored to be her twin.

BRIE: The care, compassion, and empathy at the core of Joyce and Judith’s story will stay with me forever. Joyce dearly loves her sister, and that’s infectious. We need more love in this world, especially for those to whom it’s often denied. Judith was an artist and her work is a powerful statement on being here, being a citizen of this world. She put her soul into her pieces. Her art takes your breath away. She deserves accolades and a place in history for her work that spoke in layers. These sisters are artists, and I respect them both immensely.

MELISSA: Everyone deserves the humanity and dignity of creative self-expression. I’m left inspired by Judith’s resilient spirit. She may never have heard the words “art” or “sculpture,” but she thrived in an environment where making art is celebrated. It was my privilege to cowrite this extraordinary story and to bring Judith’s world to life.

Ceramics at Creative Growth

Learn More About the Creators